Sasayama is many things from the home of traditional Japanese culture and natural beauty to a bed town for workers commuting to the nearby Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe metropolitan area. But it is also an important agricultural area famous for many delicacies. We’ll get to those delicacies next time, but today I’d like to introduce the Autumn Festivals of Japan that celebrate the agricultural harvest, specifically the one held in my area every October.The autumn festival is a time to give thanks for the harvest, as it common in agricultural communities around the globe, but as in everything else, Japan has its own special way to do so. This is when the Japanese get out those huge “portable” shrines to meander throughout the local streets. (“Portable” in parentheses because if you spent the day helping to carry or pull one, you’d soon realize that they are not all that portable.) This is a celebration of the harvest, a traditional religious event to give thanks, and a gathering of people to form and renew bonds. It is a respite from everyday labors to spend time with the local community.

Our festival is traditionally a two-day event with a kind-of warmup day and then the main festival day. One of my older neighbors told me that when they were young, they would spend the entire warmup day carrying the heavy Omikoshi and visiting the six surrounding villages that gather the next day to celebrate together, drinking large quantities of sake. Unfortunately over the years even most manual laborers are not nearly as strong physically, so the warmup day has been abbreviated or vastly simplified, but we still get a good workout on the main day. The following photo shows us carrying the shrine through the local streets.

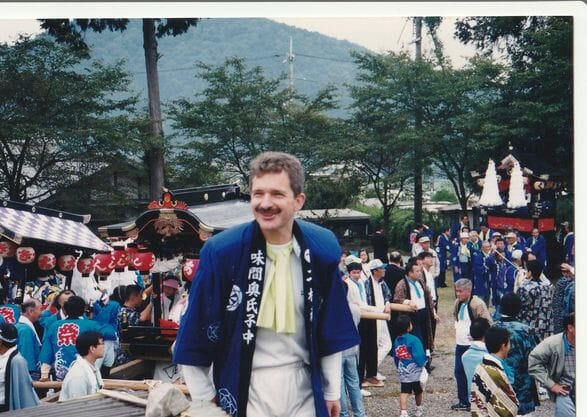

There are actually two different types of portable shrines, the Hikiyama (a huge portable shrine on large wheels) and the Omikoshi (a shrine that is carried, as shown in the photos). Elementary kids ride on both playing musical instruments—drums, chimes, and flutes. For years I helped by teaching the kids to play the flute during the weeks before the festival when they gathered to learn the music. It’s a big deal for the kids and a lot of work for the parents too, but it creates memories for them and an affinity for their home area, which is important to most Japanese people. Even if they have never lived there, their traditional family home remains important.

The main day of the festival goes something like this. The officials start gathering at 5 am (when I helped as an official, we started with a cup of sake) to get everything ready in time. Then everyone gathers at 8 am to start the procession to the local shrine where seven local villages gather. The final challenge is to get the Omikoshi up the steps to the shrine, as shown in the following photo.

At the temple, prayers are said and rice cakes are thrown for everyone to catch. (If it’s got a number on in, you win a prize.) This is also a good time to catch up with people from the surrounding area. Decorated rice cakes and sake are given to the priests to be blessed and then returned to individual villages for everyone to enjoy. After all of the official events are finished at the shrine, everyone returns to their own village where they eat and drink too much and then carry and pull the portable shrines through the village for everyone to enjoy, while continuing to eat and drink too much. The best part is after dark when all of the lanterns come on. BTW, traditionally sake blessed by the gods is considered sacred. Sake is often offered to the gods and drinking sake is often still used as a purification rite.

At certain times when we lift the Omikoshi above our heads and bounce it up and down to put on a show as a symbolic thank you and as a way to celebrate. At the end, we repeat this many times to end the festivities.

A few additional comments: First, within reason, eating and drinking too much is not a problem because you’re definitely going to burn it off by the end of the day. Second, the younger people through about 50 years old carry the Omikoshi and the older people pull the Hikiyama. But there are always a few people like me that hang on and refuse to gracefully retire from the Omikoshi. It’s just too much fun. A couple of years ago, the guy next to me was 70 years old, and much to my chagrin he was doing better than I was. Finally, autumn festivals vary greatly by area, even in the same region, e.g., even within Sasayama, so it’s always interesting to watch them where ever you go to see the differences. Even in the same area, they are often held on different weekends, so you can catch more than one if you do your homework.